City of God

A harrowing depiction of a life in which innocence will get you killed.

Let's get one thing clear. City of God is NOT the Brazilian Goodfellas. To describe it as such is to do the film a huge disservice, suggesting that it is nothing more than an imitation of Scorcese's masterpiece, the story of Jimmy, Tommy and Henry simply transplanted to Rio de Janeiro. No, this is a masterpiece in its own right, though there are undoubted similarities - not least the quality.

Not many films can claim to be in the same class as Goodfellas, but this is one of the few. Admittedly, in the final analysis, not quite as good, but City of God is punching well above its weight. While Goodfellas features some of the best actors to grace the silver screen (Mr. De Niro, please step forward), and is directed by the finest director in Hollywood, City of God is peopled by unknowns and amateurs, and directed by relative newcomers (Fernando Meirelles and assistant director Kátia Lund). Like Stallone's Rocky, the amateur has taken on the champ, and lost only on a points decision.

Set in one of the many ready-built towns, known as favelas, around Rio de Janeiro, Cidade de Deus is a harrowing depiction of a life in which innocence is an unknown word, and naivety will get you killed. Unfortunately, so will walking down the wrong street and looking at the wrong people in the wrong way (apparently for having the audacity to look at all, in the case of the film's chief antagonist.) In the words of Vaz Blackwood's Rory Breaker - "You're gonna have to work pretty hard to stay alive."

Several of these favelas were constructed throughout Brazil in the 1960s to cope with the massive overcrowding problems in Brazil's cities. Millions of people were shunted into these new towns from the inner city shanty towns, mostly black people, who were, and indeed still are, considered a social underclass in Brazil. Built from the cheapest materials to low standards, some of the favelas weren't much of an improvement on the slums they were built to replace (indeed, some of them were contiguous with the shanty towns).

The titular City of God is a breeding place for crime. Populated by under-privileged, poor, beaten down people, and controlled by the street gangs, with little chance of escape. Children are exposed to death and crime from birth, and there are few in the city who can earn enough to live on without having to supplement it with illegal activities. Despite this, and against all expectations, hope remains, and this hope is the central theme of the film.

Based on the eyewitness accounts of Paulo Lins, our story starts in the 1980s - with a chicken. Having escaped from the leaders of the drug gang, who intend eating it, said chicken makes a run for it through the streets of the city as the dealers (all of whom are no older than their late teens or early twenties) take chase, guns firing in an attempt to take out the emancipated pullet, either unheeding or uncaring of the danger to bystanders (both options seem equally likely).

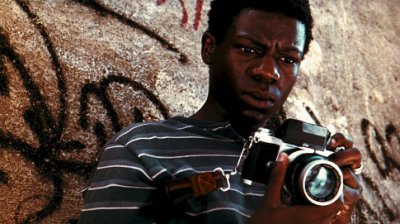

We cut to the film's protagonist, budding photographer Busca-Pé (Matheus Nachtergaele), known as Rocket, as he tells his companion of his fears of running into Lil Ze (Leandro Firmino da Hora), the leader of the largest gang in the city, whom he believes wants him dead. As they turn the corner, the chicken runs past them. Not far behind are Ze and his gun-toting buddies. Uh-oh indeed. As Ze yells to Rocket to catch the chicken, several armed police officers appear at the end of the alley, and an alarming number of deadly weapons are raised from either end of the street, with our hero caught in the middle. Time stands still, and the camera executes a deft 360° around Rocket.

We now find ourselves back in the '60s, in the early years of Rocket's childhood, and Nachtergaele begins his narration.

We are treated to a history of guns, drugs, crime and death. Lots of death. Rooted firmly in fact, the story is told against the background of the racism inherent in Brazilian society in the 1960s, particularly in the police, a massively corrupt organisation which tends to leave the favelas well alone unless they have no choice, and the 40 000 violent deaths that occur in Brazil each year.

Beginning with the story of Rocket's brother and his two friends, the three being the most notorious gang members at the time, we are left with no illusions as to the harshness and reality of life in the favela. After a robbery gone very wrong, the three friends are forced to flee the slum, and it is at this point that the young Rocket decides to turn away from the life his brother has led.

We follow Rocket as he grows up, and the face of the city changes - once ruled by several warring gangs, one man, the psychotic Lil Ze (even more unstable than Joe Pesci's volatile Tommy) takes control over most the city, and the peace of the gun rules for a time. This is shattered when he decides to go after the last piece of turf that he doesn't control, and all hell breaks loose. People joining up with the gangs for reasons of revenge soon lose sight of why they joined, and fully embrace violence for violence's sake The lives of thousands of people are irreversibly changed, or, more often, brought to a premature end. Life is cheap in the City of God.

Yet beside all these horrific events are put moments of humour, warmth and hope - Rocket and his friends enjoying themselves on the beach, building relationships, making plans. For a large part of the film, our narrator's main concern seems to be with his virginity, and plans for divesting himself of it. He is an intelligent and talented young man, who will not follow the path of most of his contemporaries if there is any way to avoid it. His ticket out is his passion for, and skill in, photography (some of the most potent scenes of the film are seen from the point of view of his camera). Getting a job at a Rio newspaper is the possible beginning of a new life for Rocket, and it is he that provides a lift from the despair of the City of God, proving to the viewer that all hope is not lost.

Given the high body count, few characters stay in the film for long enough for us to identify with them, but the central characters are so strong and well-written that they will remain with you for a long time to come. It is the characters that are the film's real strengths - Meirelles' gives his characters a humanity that allows the viewer to emote and identify.

Chief among these memorable characters is Bene, Lil Ze's lieutenant. Played excellently by Philippe Haagensen, Bene is a voice of reason, an antithesis to Ze's 'let's kill everyone' attitude. Popular, and beloved of the inhabitants of the favela, Bene is the most vibrant character in the film, and the viewer can't help but wonder what would have happened had he gone down a different road.

Meirelles' direction is sharp and energetic, and given the many gun fights and acts of violence the film contains, it is all the more to his credit that he has managed to shoot and edit (much of the editing is very inventive) each in a different, yet equally effective, style, meaning that each is as interesting as the last. The photography is also excellent - the early scenes are imbued with a rich golden glow, and as the story progresses, this changes to washed-out hues, in keeping with the worsening nature of life in the city.

The true genius, however, of the film lies in the casting. Using mostly amateurs taken from the streets of favelas, recruited through open-access workshops, Meirelles' has given the film true authenticity. Encouraging the children to improvise, the performances are amongst the most natural and compelling you will see. Watch out in particular for the scene in which Lil Ze catches up with the 'Brats', a group of kids around the age of 12 who are carrying out robberies in the city, against Ze's rules. Forcing two of them to choose whether to be shot in the foot or the hand, it is a haunting scene that will stay in your mind for a long time to come.

Full of recriminations and reprisals, some genuine shocks, and overflowing with vitality, Meirelles' film is a fine piece of modern cinema. What stops it from being truly great is that it lacks any kind of introspection. The City of God is full of the same people doing the same stupid things, generation after generation, and the film presents no suggestions on how things can be made better. That said, there will be few better films this year, if any, and I urge you to get down to your local multiplex and see it.

It's pretty obvious that this film contains the full 5 Combined Goodness Units.

Leandro Firmino da Hora (Lil Ze)

Philippe Haagensen (Bene)